‘untitled BLM’: Emory student steps into vulnerable space to create winning photo

EGHI joins the National Museum of African History and Culture in celebrating Black artists, their art and its “relationship with justice” and health equity.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture invites us to celebrate the Black History Month 2024 theme, “African Americans and the Arts,” and arts’ relationship with justice.

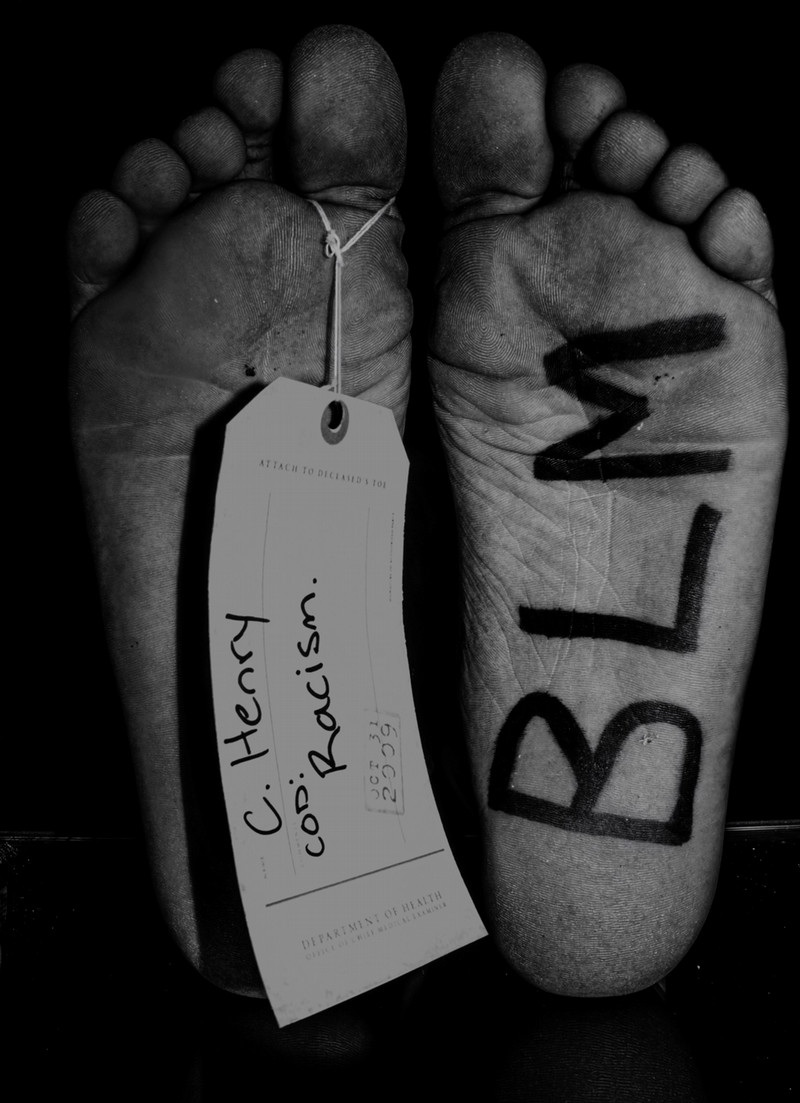

Inspired by this theme and the leap year, EGHI spotlights Cody S. Henry, a visual artist who studied film and photography while earning his MPH from Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health. In 2021, Cody submitted his photo, ‘untitled BLM’ to EGHI’s Student Global Health Photography Contest and was among the top entries selected by a panel of expert judges. We recently had a chance to catch up with Cody to learn more about the artist and advocate who was both behind the lens for this winning photo and the subject of this powerful, painful, and deeply personal leap into the subject of racism in America.

Cody S. Henry, MPH

Excerpts from an interview with Cody S. Henry (CH); conducted and edited for Black History Month 2024 by Amy Rowland (AR), Communication Director.

AR: Most of our photo contest entries feature a global health challenge that our students are observing. You are both the observer and the subject of your photo. What made you decide to approach the topic by turning the lens on yourself?

CH: I often use myself as subject in my photography. My life and lived experience is not separate from the world… the psycho-social issues happening in the world, outside of me, also affect me. How that drives my photography is that I’ve always wanted to create art that includes myself, where I can see me, but where folks are also able to see themselves.

AR: Your photo has another mark of distinction from other contest entries over the years in that it is “staged.” In fact, you stage your own death. That seems like a vulnerable space to be in. Tell us about your creative process that led this concept?

CH: It took some time. It definitely was a vulnerable space to step into. Statistically speaking, racism will probably be a contributing factor to my death, even if down the line, because black men have a lower life expectancy. Black queer men have a lower life expectancy, and once we trace the underlying causes down, race is a mediating factor. This photo is a coming to terms of the reality I have already lived and that I know.

This process was a coming face-to-face with my own cause of death as racism. I had to accept my own death if I wanted to move forward and help make this not my reality. Circling back to my work in public health, black gay men who have sex with men in Atlanta, for example, have a 50% chance of developing HIV over the course of their lifetime. That is a scary statistic to research, but it is a whole other world to live.

AR: At the time of the contest, you were at Rollins and U.S. CDC had issued a statement declaring racism a public health crisis in the U.S. Did this step by our nation’s public health agency play a role in your focus on this topic?

CH: I saw the statement as a moment when the science was catching up with society… especially in the wake of 2020 (ref. George Floyd’s death May 2020), the racial justice protests that summer at the same time as COVID-19. These events occurred 4 years after my first MPH class at Rollins in which I learned that the black infant mortality rate was 2.5 times higher for black babies than white babies in America. We’ve known that racism is a public health crisis; it’s a global health crisis. The data, the hard science has been there. My piece was a response to the shock of it all, the cultural shift that I was feeling.

The statement… it was important and needed, but it was a response to a cultural shift. It felt like a campaign and strategy moment rather than any explicit thing or response to the epi or health outcomes.

AR: Communities of color disproportionately experience violence that can lead to poor health outcomes. Systemic racism is recognized as one social determinant of health that drives health inequities, such as violence, especially affecting young men. Did you have conversations with your mom about the risks of violence and racism in society? How did she best prepare you to fly and thrive?

CH: Taking a step back, even before the forming of my sexual identity, I was still a young Black man growing up in America. My mom did talk with us about the adversity and barriers we would face. She did everything she could to protect us and raised 4 beautiful, successful Black men. Early on, after I shared my sexual orientation with my mom, it added an additional layer of fear that she experiences and lives with. We have had conversations about how she has extra worry for me compared to my siblings because of the additional intersectionality of identity - of who I am - that can bring more adversity. At the same time, she supports me to live my life, including living abroad in India, which was an anxious time for her.

With so much adversity that can come my way, it’s a daily active choice to maintain my integrity, my joy, my smile.

Cody moved to Washington, D.C. last year where he works at a local non-profit as a Research Coordinator and youth advocate to reduce the burden of HIV through direct outreach, education access and social sevice provision. Cody began his career in HIV treatment and prevention work focused on HIV storytelling and learning how to translate personal narratives into role model stories. He speaks to HIV prevalence data and health disparities experienced by black and brown communities like a seasoned health professional. He describes how art plays an important role in his life and in society to communicate emotions, build community, and inspire action. Where art meets health sciences - meets public health - meets racial social justice, this intersection is a space where Cody is confident and flourishing.

###

2021 EGHI Global Health Student Photography Contest Winner "untitled BLM" by Cody S. Henry, Rollins School of Public Health, MPH ‘22

Autopsy photo depicting foot soles of “C. Henry.” The right foot has a toe tag that identifies the cause of death as “racism” and the left foot has “BLM” written in black. In 2021, the CDC declared racism a public health crisis.